Hopper

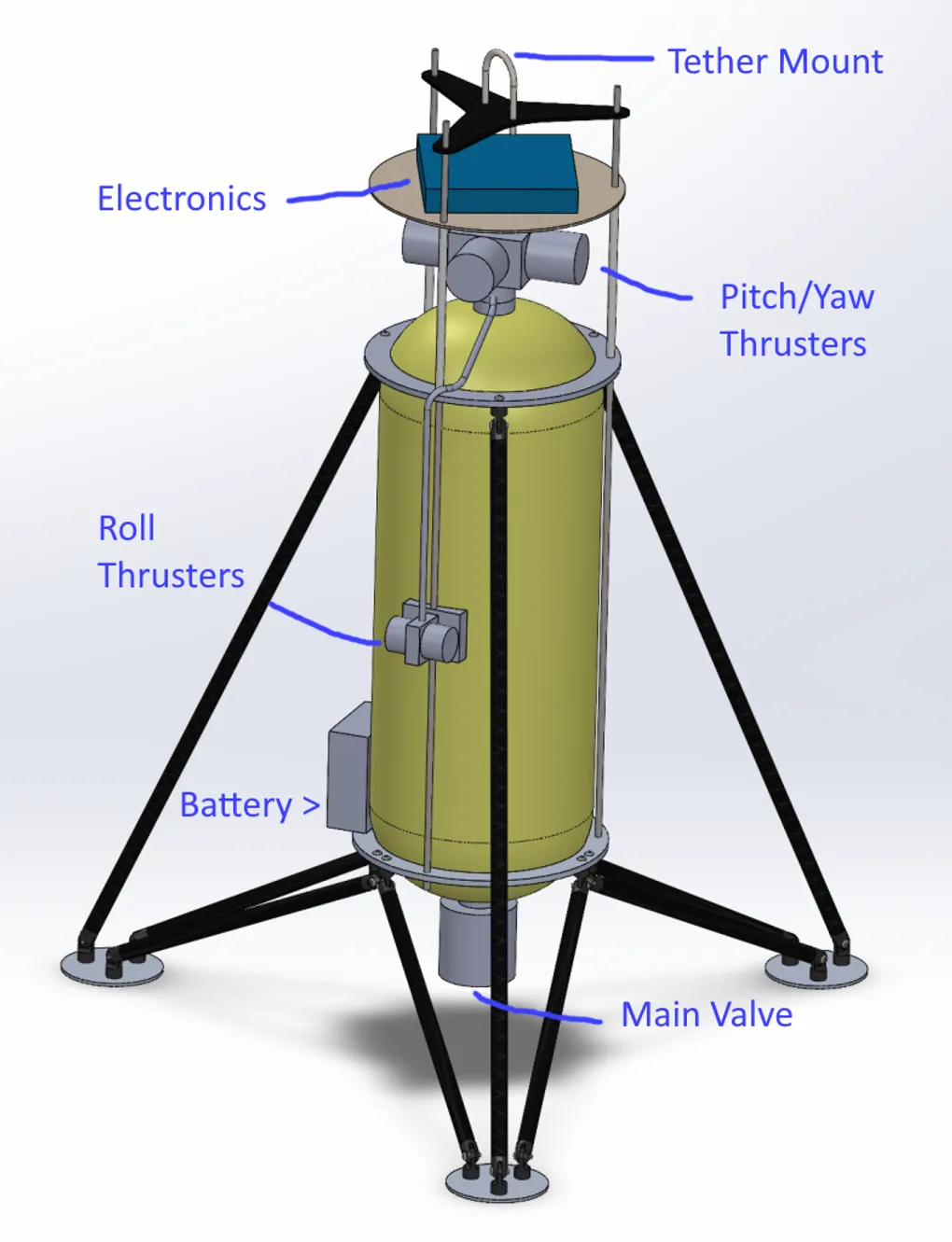

This is a vehicle that 2 friends and I have been working on since August 2022. It is a VTVL rocket propelled by pressurized CO2, weighs about 30lb empty and 60lb full of propellant, and is about 4 feet tall, with the central yellow tank being about 2.5 feet long. It is designed to be able to hover for up to 30 seconds.

The vehicle’s central yellow tank (composite with aluminum liner) was donated to our rocket team by an aviation refurbishing company, and in a previous life held nitrogen in a 757.

This means it is extremely lightweight and rated to hold very high pressures, which makes it perfect for a vehicle that is a flying tank with some valves and legs strapped on. The presence of this tank enabled this project, and 20+ seconds of flight on a propellant as inefficient as cold gas would not be possible otherwise.

While we’re all fairly experienced, a project this complex does not (and should not) get built right away after an initial design is completed. Instead, we have been working on validating different aspects of this vehicle separately, well before the vehicle build actually begins.

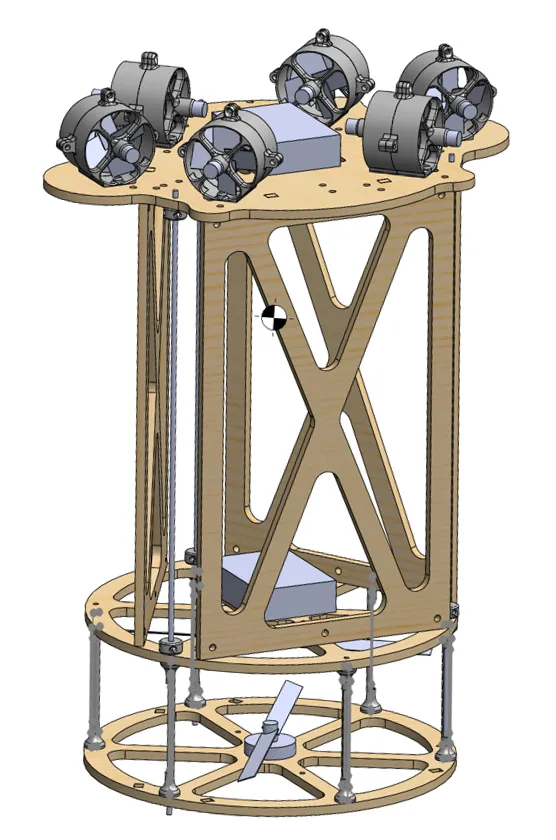

My contribution to the project has been: high-level design decisions, the CAD of the vehicle pictured above, a self-stabilizing stick to learn more about closed loop control basics, and a drone design intended to imitate the control characteristics (specifically, thrust to weight and angular acceleration caused by attitude thrusters) of the eventual vehicle. Drone CAD and assembled frame (electronics and code currently WIP) pictured below.

Attitude control

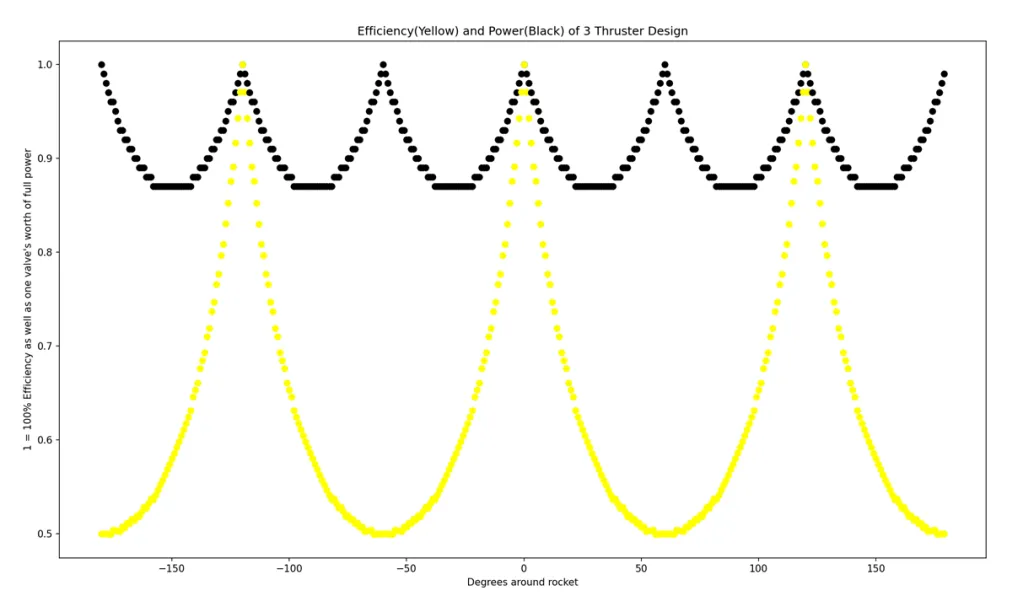

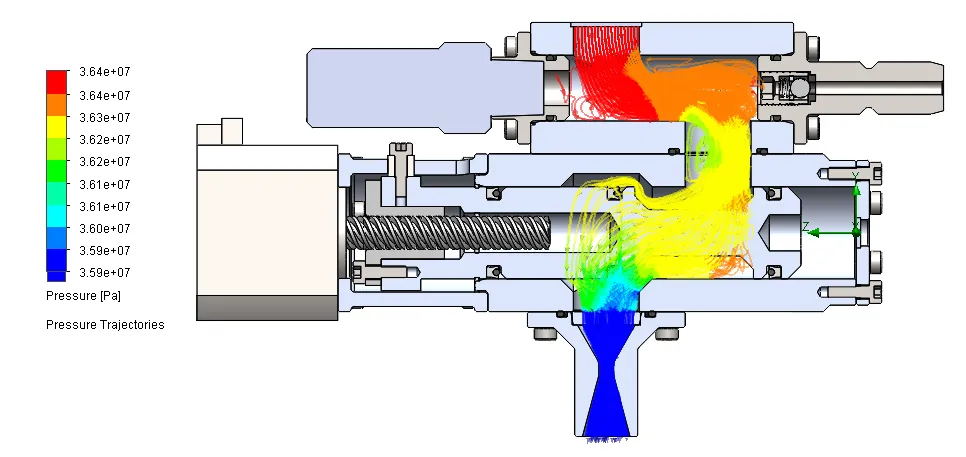

This has been the largest area of work thus far. We started out the project by investigating different attitude thruster configurations (pitch/yaw thrusters in above image), and generated graphs of efficiency and relative thrust by angle of thrust (using two or more thrusters to pitch the vehicle in a certain direction).

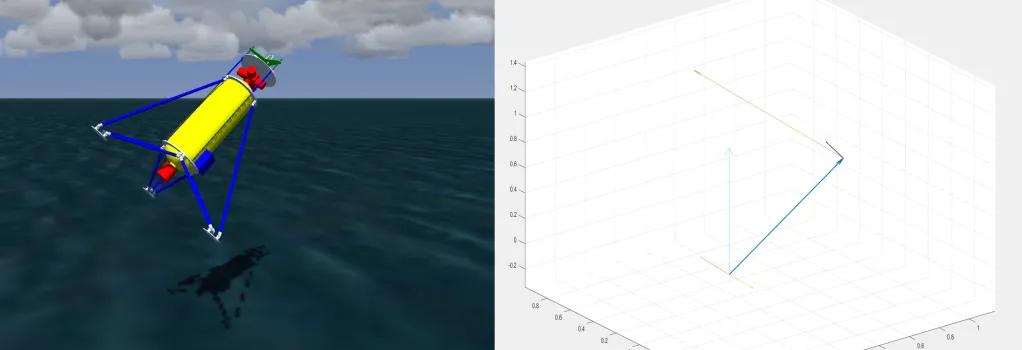

After settling on an architecture (four valves/thrusters on top of the vehicle, and two on the side for roll control), we began writing a simulation program in MATLAB, which was able to inform us about required engine throttling ability (we initially wanted to pulse the main thruster for simplicity, but determined this was not feasible for landing the vehicle safely) and attitude thruster strength (needed much less thrust than expected). Simulation program pictured below.

My own stick and drone projects have also been a significant part of our investigation into attitude control.

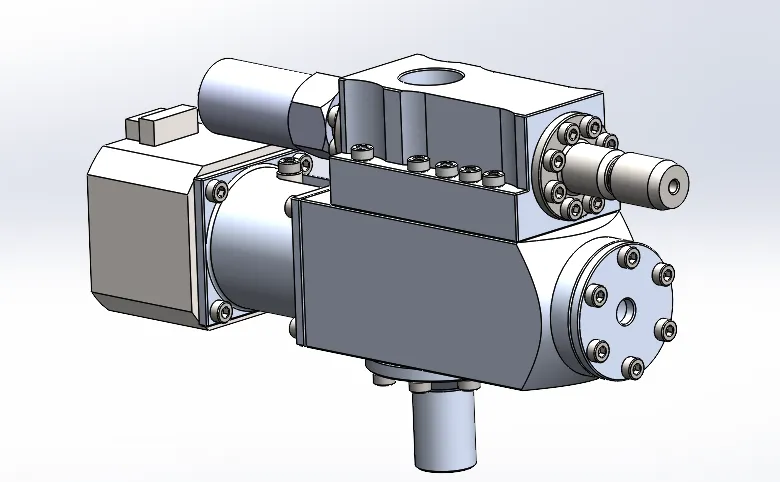

Valve design

We decided to go with custom solenoid valves for our attitude thrusters due to the high weight and cost of commercial options, and a custom stepper motor-actuated spool valve for the main thruster mainly for cost reasons. The main valve design is complete and we hope to begin machining and testing soon.

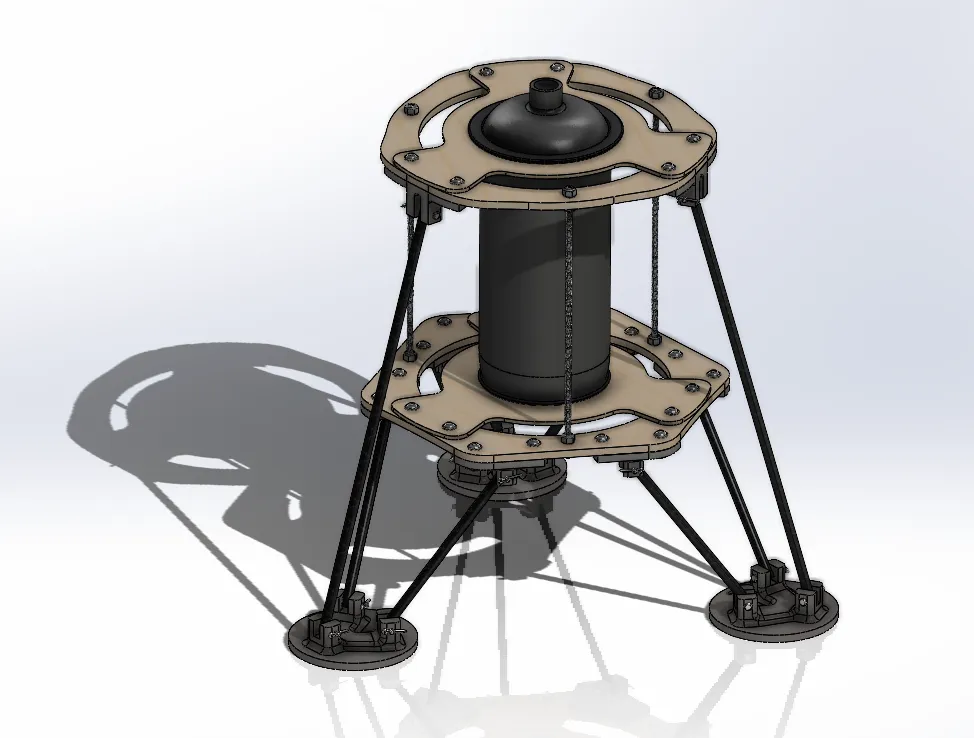

Leg design

We designed and tested a subscale assembly of the planned leg design, CAD of which is pictured below.

Our qualitative testing led to added tensioning wires on the main vehicle design, hoping to keep the legs stable and the feet facing the ground while also being able to absorb the impact of landing.

We have also put initial design work into eddy current dampers to be able to tolerate less-than-perfect landings and be easily reusable (as compared to using a crushing damper).