Weird Math

Title purposefully vague so you get a chance to think about the following.

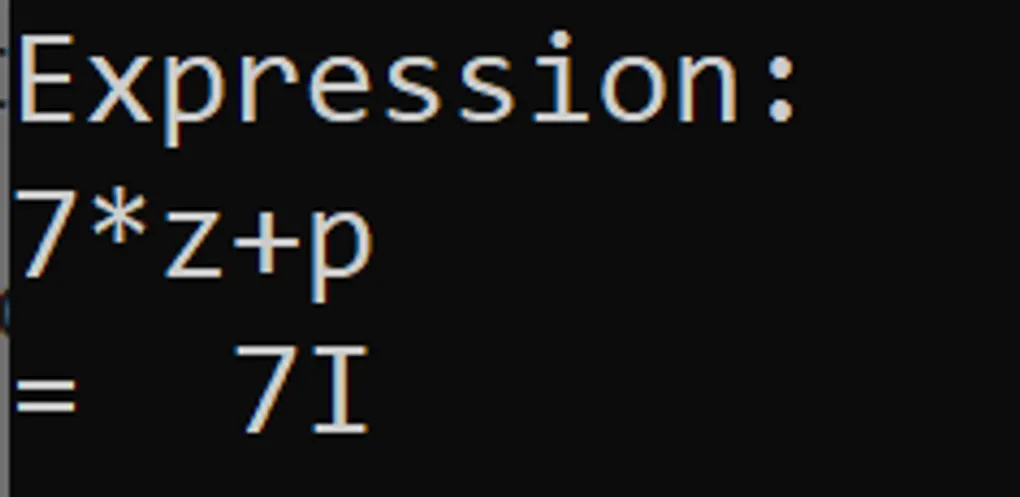

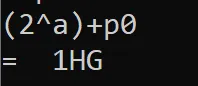

What type of math is this?

It might look complicated, but this is actually pretty simple math. So what’s the catch? Try to figure it out before scrolling down.

If you want to play around with this type of math in code and not read any boring explanations, click here

It’s base 36! If you’ve worked with other bases like binary, or especially hexadecimal, you probably figured it out. A month ago, I knew how bases worked and did some math in binary for classes, but never really did normal math in other bases just because. A friend and I wrote some base 36 multiplication problems on a whiteboard and solved them trying to work and think as much as possible in base 36. Of course, it’s not a challenge to convert the numbers to base 10 and then do the math (in the last example above, c = 12, 12^2 = 144, 144 / 36 = 4, which is 40 in base 36), but that’s not the point. The point is:

So, what can be learned about math by actually learning and working in another base? How difficult is it to actually do math in bases other than 10 (instead of converting to and from it for each problem)?

After doing math in base 36, I wanted an easy way to check my answer without converting it to base 10, and to get a feel for math in base 36 in general. So I looked for a calculator to evaluate math natively in bases besides 10. There are many sites out there to convert numbers between bases, and a few that let you select two numbers of any base and one operation, but I couldn’t find any full-fledged calculators that let you enter math the same way you can in a normal calculator. So I made my own. The scope crept to support any input base up to 36 because it was a super easy add, output base up to 112 for the same reason, and the scope crept again to support input and output in different bases to make it an easy base converter as well. Here it is. It’s pretty self explanatory. I highly encourage you to download it and play with it for a bit if you want to get a better feel for math in bases other than 10.

The below is what I learned while attempting to learn math in base 36 (but it easily generalizes to other bases). It’s pretty long and progressively more ramble-y, so just download the program above and close this page here if you’re not super interested in the idea of learning how to do math in other bases, which holds zero practical value when the program above exists, and if it didn’t you could have just converted the numbers to and from base 10 for the three times every decade you have to do math where neither side of the equation is in base 10.

Try and solve the below base 2 math without mentally converting to base 10.

11 + 10

1101 - 10

10 * 11

111 * 111

The first problem is trivial. 1 + 0 is 1, so the ones place is 1. There is no digit to represent 1 + 1, so you carry a 1 and there is no remainder, leaving us 101.

The second is also easy. 1 + 0 is 1. 0 - 1 is below zero, so you borrow a 1 from the next place up, and the 10’s place becomes 1. This gives us 1011.

Now things get a bit harder: multiplication. If you work with binary a lot, maybe you already converted the number in your head, but even if you don’t, it’s pretty easy to see that this would be a very quick problem in base 10. But how do you actually do the math? What rules can you use?

Multiplication is a different type of operation than addition/subtraction. If you think about it, there are not really any rules that you can use other than breaking the number down and using multiplications that you have memorized along with addition rules. For base 10 we have many multiplications memorized, for most STEM-y people, most combinations with both numbers lower than 10 at least. Let’s say that for base 2, all we know is that 10 * 10 = 100 and anything times one is itself.

Now we can separate the problem into 10 * (10 + 1), breaking down the second number with addition rules. After applying our only known multiplication, the problem turns into 100 + 10, which is trivial.

111 * 111 is doable by breaking the number down into only (x * 1) and (10 * 10), but let’s generalize our multiplication rule just to make things easier: If you multiply two numbers that are both ones followed by a number of zeros, the result is a one followed by a number of zeros that is the number of zeros of the two numbers added together. Note that this now encompasses the “anything times one is itself” rule; one has no following zeros, so anything times one is that number plus no extra. So our only two rules now are that things can be split apart into numbers that add up to the original number, and the one followed by zeros rule.

The one followed by zeros rule means: 10 * 100 = 1000, 1000 * 1000 = 1000000, 1 * 2693 = 2693, etc.

Attempting 111 * 111 again:

111 * (100 + 10 + 1)

= (111 * 100) + (111 * 10) + (111 * 1)

= (100 * 100 + 10 * 100 + 1 * 100) + (100 * 10 + 10 * 10 + 1 * 10) + 111

Now broken down enough to apply the multiplication rule and turn the problem into just addition:

= (10000 + 1000 + 100) + (1000 + 100 + 10) + 111

This is now easily solvable with addition rules.

So we figured out how to do math in base 2, assuming we don’t know anything about base 10. It turns out that our two rules (and the implicit rules of breaking numbers down into parts) are simple enough that they work when generalized to any base, and are all we need to do any multiplication of integers, in any base.

Before getting into base 36 math, it’s worth noting that the only reason we picked base 36 is because it is very easy to represent its digits: just the numbers plus the alphabet. We just as well could have done base 12 (aka dozenal), base 16 (aka hexadecimal), or even a base below 10. However, we later realized that base 36 does have some properties that make it useful (or at least interesting) as a base to do math in. Namely, 36 is a square with a bunch of factors (9). 16 is also a square, but only has 3 factors. 12 is interesting for the same reason, with six factors.

Another quick note: Before continuing, I highly recommend downloading the calculator program mentioned above and playing around in it for a few minutes, if you haven’t already.

So now, let’s try this base 36 problem:

7 * Z + P

So, where do we even start?

I found it helpful to have a chart of the base 36 digits and the base 10 numbers represented alongside each other. This goes against the “no converting into base 10” rule, but when working with digits beyond the numbers, you need some type of crutch to lean on. Let’s limit ourselves to only using the chart to break down numbers.

(Right click -> open image in new tab to view in more detail. Notice each number is “digits”, not “value”. This is to drive a point home that you almost certainly already realized: It is impossible to write/communicate values, we can only write/communicate representations of them in various different bases. The correct meaning only comes across if both sides know the base, symbols, and mapping of symbols to values, involved.)

The second (and last) new rule is a clever one. I call it “incrementing” or “decrementing”.

Z * 1 = 0Z (leading zero normally not shown)

Z * 2 = 1Y

Z * 3 = 2X

Notice any pattern?

A similar sequence in base A:

9 * 1 = 09 9 * 2 = 18 9 * 3 = 27

In both of these, the 10’s place increases by 1 and the 1’s place decreases by 1 for each larger number. Take a second and try to figure out the rule to generalize this behavior before you look at it below. This sequence, back to base 10, might also help:

Y * 1 = 0Y

Y * 2 = 1W

Y * 3 = 2U

Here is the rule:

(10 - x1) * x2 = (x2 * 10) - (x2 * x1)

Base A: 9 * 2 = (10 * 2) - (1 * 2) = 20 - 2 = 18

Z * 3 = (10 * 3) - (3 * 1) = 30 - 3 = 2X

Y * 2 = (10 * 2) - (2 * 2) = 20 - 4 = 2W

U * 6 = (10 * 6) - (6 * 6) = 60 - 10 = 50

Explained in words, this gives us a way to drastically simplify multiplications between a number under 10 and some smaller number. The rule actually works for any two numbers, but it only really saves you time if you’re multiplying something a bit under 10 with a small number. This rule basically transforms a multiplication into a subtraction; you only need to know the results of multiplications that are almost always less than 10, and 10 minus that result. This rule will make a lot more sense once we actually start using it.

To recap, we can use the following rules:

Breaking down numbers into constituents (addition)

(x, followed by n zeros) * (y, followed by m zeros) = x * y, followed by (n+m) zeros

Multiplications with a result below A

Incrementing / decrementing

For now, I stopped after figuring out multiplication and wrote the calculator program. Maybe I’ll get to division eventually, but it would just be more of the same as multiplication: develop algorithms and apply them, which I already did in a vastly more repeatable way by writing them into code. Some notes, though:

There are way more non-repeating decimals in base 10 compared to base A because of how many more factors base 10 has. We are used to everything without a 5 or 2 involved being repeating. In base 10, there are 7 factors instead of two: 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, C, I. Also, 3 being a factor means there are a lot more finite, multi-digit decimals (in base A, 1 / 4 = 0.25. Four isn’t a factor of 10, but 2 is a factor of both 10 and 4, so 1 / 4 is non-repeating. Every multiple of 3 is like this in base 36.). I’d encourage you to play with factors and decimals in the calculator and see what comes up.

A side endeavor of the above efforts was thinking about bases even crazier and less practical than base 36. Fractional or decimal bases were discounted pretty quick because you have to bend the definition of a base by a lot; bases are normally defined as having the same number of symbols as the value that 10 represents in that base. You won’t really get anywhere if you try to build a number system with 1/2 or 0.1 symbols. However, you can make something half-sensible if you use n = reciprocal of the base digits. That would mean 2 digits (0 and 1) for base 1/2. You can represent all real numbers this way; the representation of any number is just the number in base 2 but flipped over the decimal place (because 1/2 = 2^-1, and (x^-1)^-1 = 1). So fractional bases where the fraction is a reciprocal of an integer are kind of just boring. I might revisit non-integer-reciprocal fractional bases (be careful not to say this term around any normal person with who you might want to talk to in the future because they will be around you in the future only when compelled to by an authority figure) in the future if I’m especially tired of working on things that have any minuscule semblance of a real-world application.

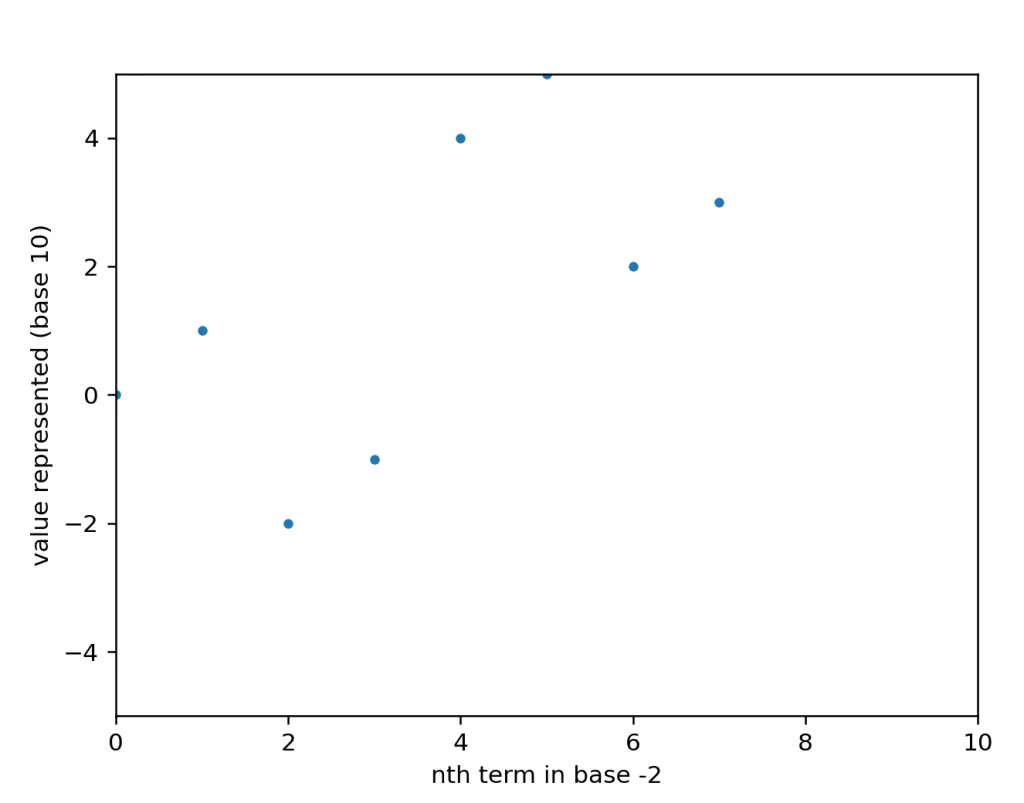

My final stop so far on the road of impractical bases was negative bases. These sort of have the same problem above - you obviously can’t have negative two symbols in a base system - but hold more interest because it’s not immediately apparent whether all real, or even integer, numbers can be represented. For base -2, the 1’s digit is 1’s, the 10’s digit is how many -2’s there are, but then the twos digit is how many +4’s there are, because a negative times a negative is a positive. So the value flip flops between positive and negative at each place in a given number. Here is a list of the first few base -2 numbers and their decimal representations.

0 0 1 1 10 -2 11 -1 100 4 101 5 110 2 111 3 1000 -8 1001 -7 1010 -10 1011 -9 1100 -4

So.. At least there are no repeats, which is nice?? But on the other hand, we’ve gone up to the 13th number in the sequence, and 6 hasn’t even shown up yet…

It turns out there’s actually a very beautiful pattern going on here, and to you who has come so far, I’d like you to try and figure out what type of sequence it might be before scrolling down. No code to help out this time.

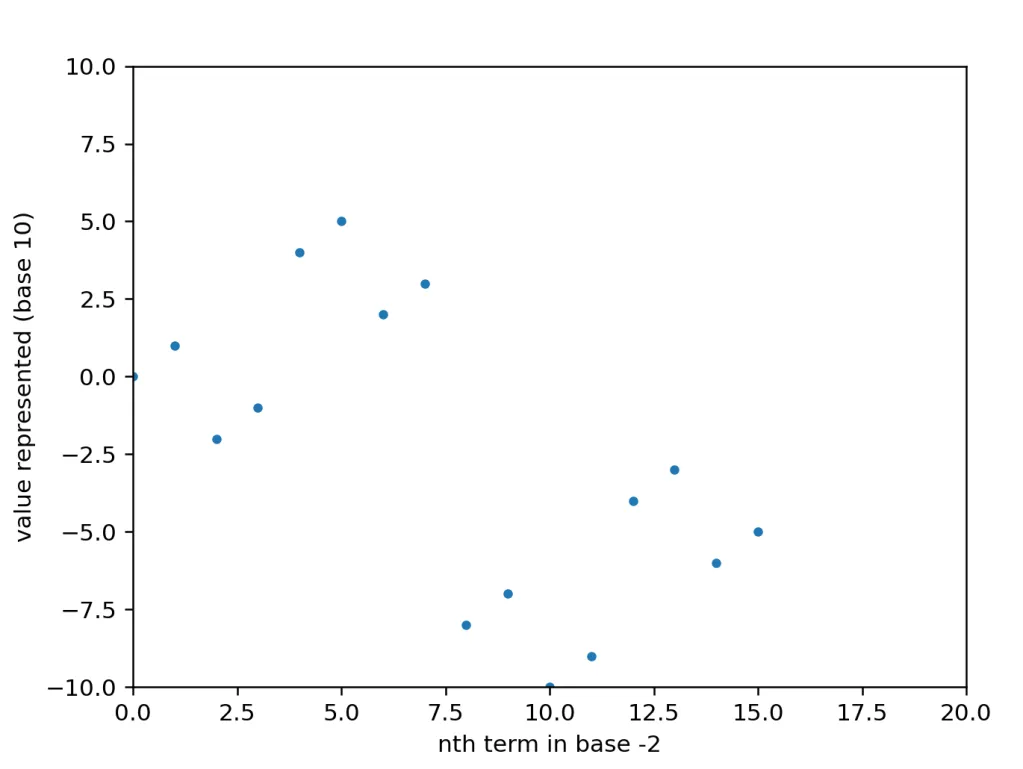

That no code thing was kind of a lie, I did write some to plot the value represented in base -2 on the y axis and value represented in base 2 on the x axis (aka the nth number in base -2 or base 2). This code can be found as neg2.py in the same directory as the base calculator if you want to play with it. Here are the first 10 numbers.

Hmm.. Well, we know it’s right because it lines up with the list above: y(0) = 0, y(1) = 1, y(2) = -2, etc. But that’s sure a weird shape. There’s two parallelogram shapes, and it looks like all the numbers above about 8 are out of our view (this is on purpose). It looks like there’s an upwards trend though, so maybe they’re above 5? Let’s expand the view to 20..

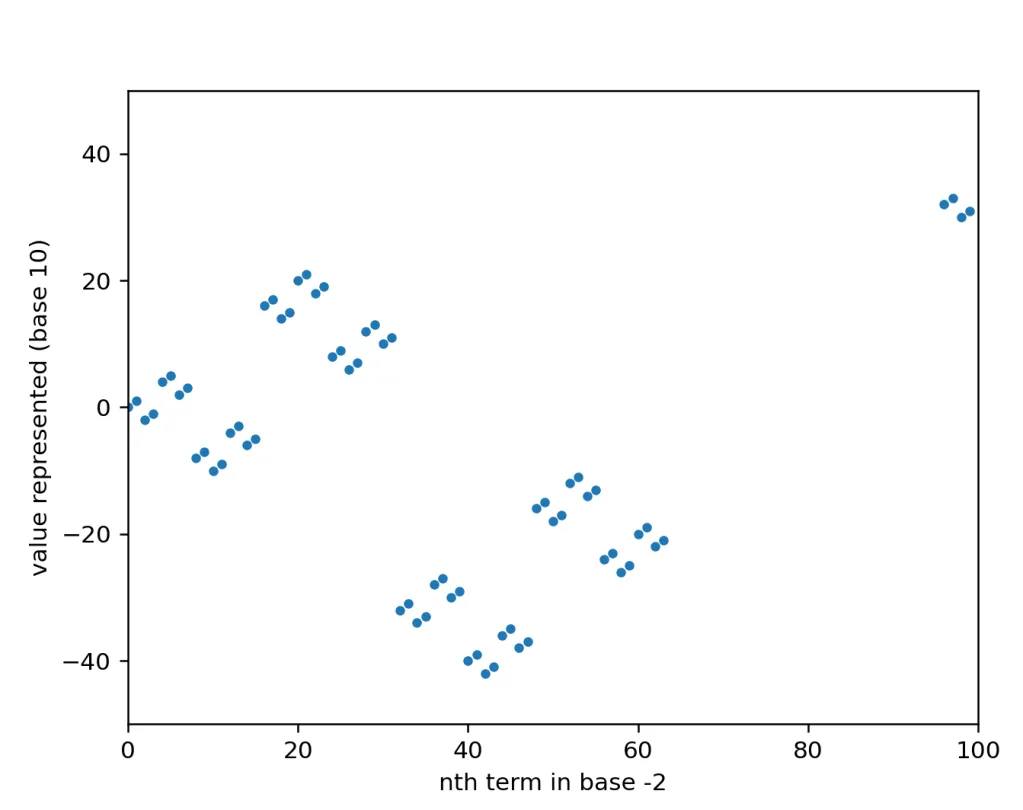

Nope, turns out they were actually way negative. And they made another of the same shape. And then the next few made another of that shape and were a bit less negative. And now, the four shapes almost look like they’re making up a bigger version of the same shape. Wait, does that mean…

100 terms:

Fractal!!!

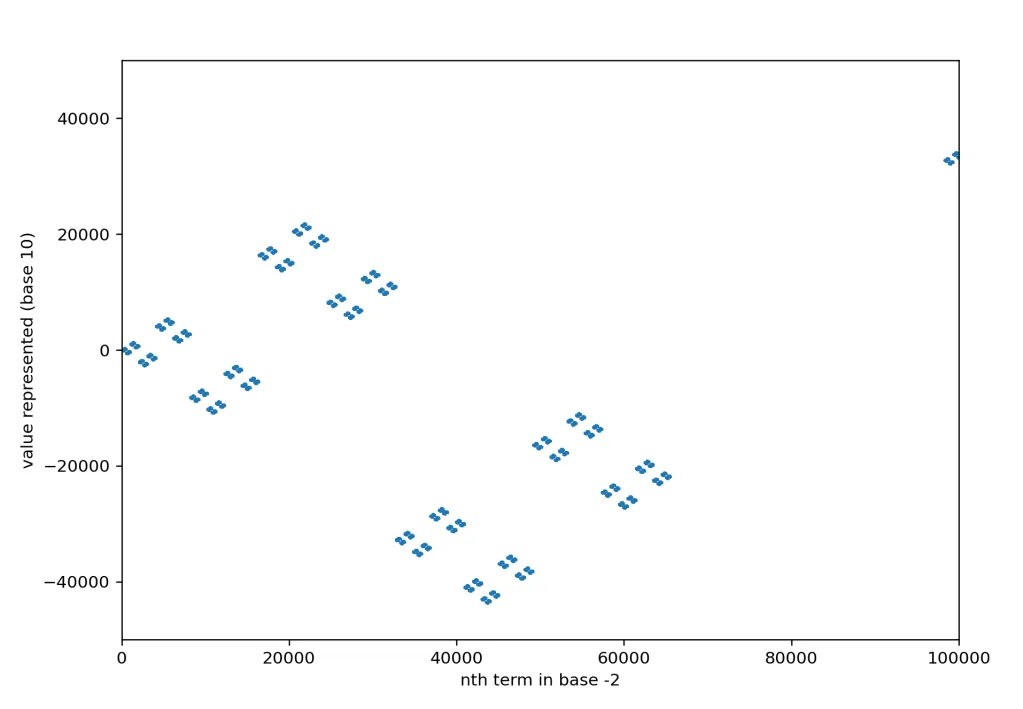

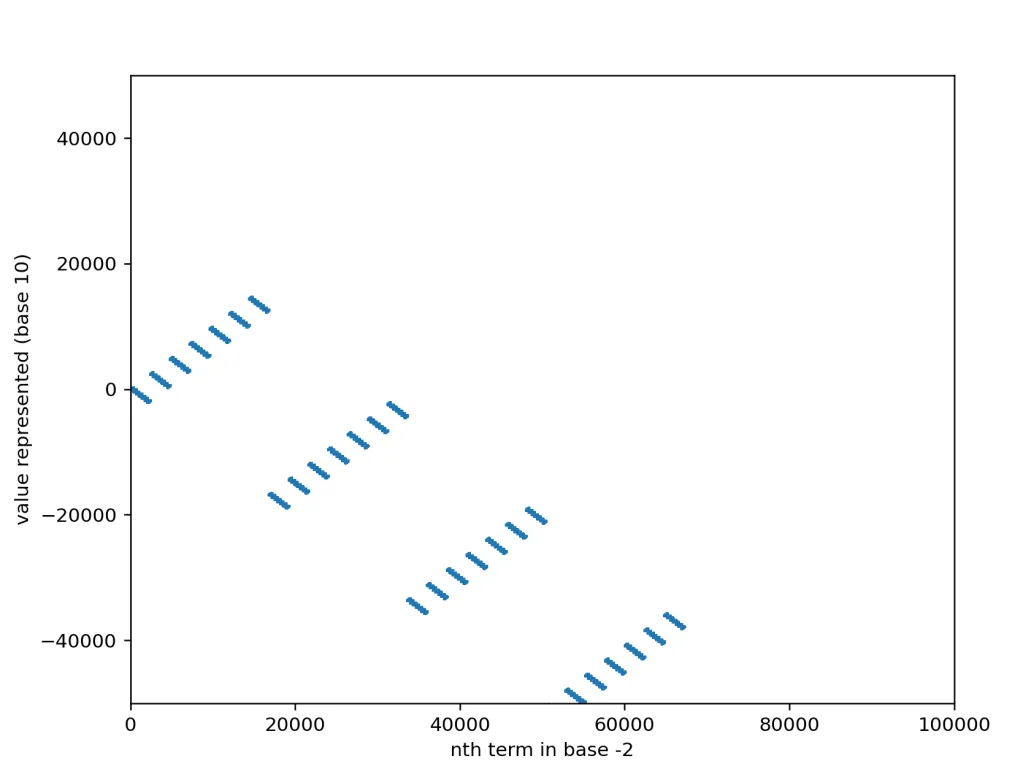

100,000 terms:

Glancing quickly at this graph and the one above it, you would think I pasted the same image twice. But there are a lot more dots in the second one. A whole lot more dots.

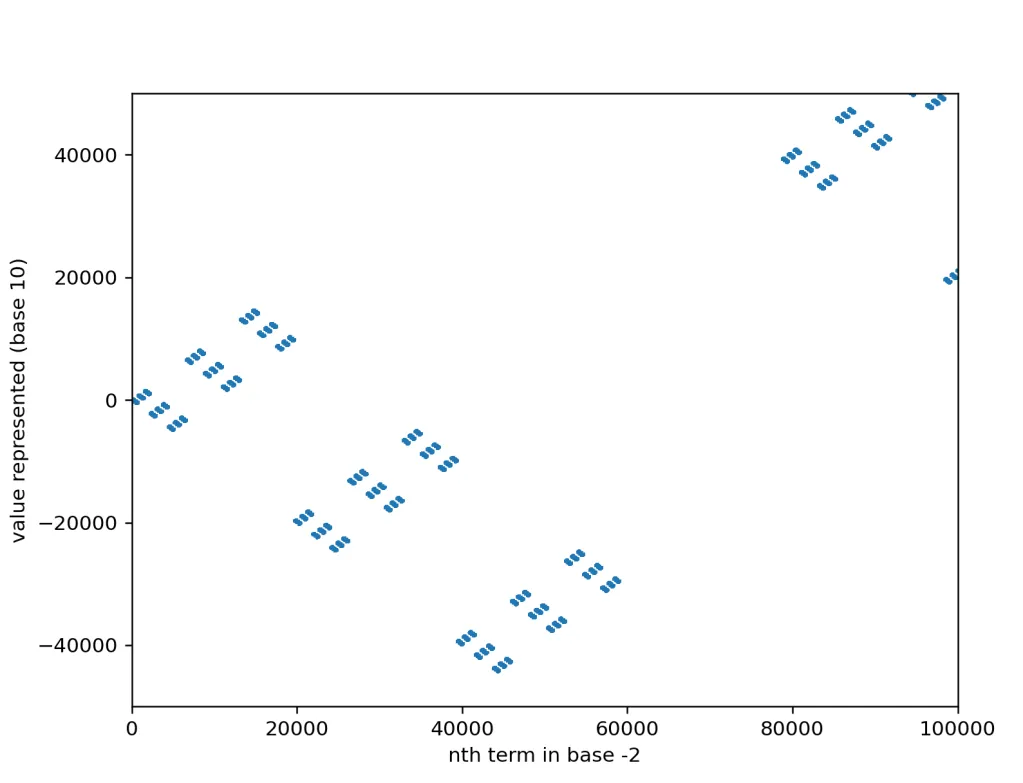

It might look like a pattern that has 4-way symmetry instead of 2, but really it just reverses direction every other… rectangle? point? Who knows. At the smallest level you can see that each group is made up of two things (dots, or rectangles, fractal don’t care). Presumably the other negative bases are the same: n groupings at the smallest level, and zig-zagging after every grouping. Here’s the -3 fractal for 100,000 terms:

And our suspicion is correct.

-7 fractal for n=100,000:

Now that the groupings are more numerous, it makes it easier to discern some properties of the general shape. We can see that it appears to hit all integers, in a roundabout way (This is confirmed with more detailed analysis of the data set). We’re at n=100,000 and it looks like it’s only gotten up to positive 20,000 or so, but we know it’ll hit those numbers on the next pass when it starts going up instead of down at the largest level.

Also, the biggest zig-zags are always on powers of the base. 2^16 = 65536, 3^10 = 59049, both graphs make a “turn” at the highest level right around those numbers. This actually makes a ton of sense: The negative bases flip-flop, and the largest flip flops are when they get a new digit added on the front, which either makes the whole number very positive when it was very negative, or vice versa.

Another interesting property is that these fractals hit all the positive and negative integers as outputs with just the positive integers as inputs.

I haven’t graphed this, but the fractal continues down below 1 on the negative x’s side. There, it would approach zero as x approaches negative infinity (an increasingly negative exponent always means something is approaching zero. The exponent isn’t 1:1 with the x value, but it is corelated (something to do with the log of something…)). The maximum and minimum bounds on the above graphs sure look like y = x and y = -x to me, but this asymptotic behavior suggests they’re not quite linear, even if they look like that for large scales. It’s interesting that this behavior is different from positive bases, which cover all of the negative numbers on the left side of the graph, and all of the numbers -1 < x < 1 right around zero. Instead, negative fractals take the whole left side of the graph -inf < x < 0 for fractions, and the whole right side 0 < x < inf for integers.

And this is where it ends, for now. If you have read this far you might be interested in continuing down the rabbit hole. My next steps if I ever get to them (unlikely) will be looking at the left side of the above fractals, then trying to extend the “base” function to be continuous (using the log function somehow), like the gamma function is for factorials, and then seeing if there’s anything special about decimal/fractional bases (probably not), (integer + decimal) bases (maybe?), and negative decimal/fractional bases (who the hell knows)(I’m sure there are some great youtube videos out there on at least a couple of those, but figuring out yourself is so much more fun (and time consuming)). I really want to see what the interpolation of the fractal plots looks like. If f(2) and f(3) are so clearly different and well defined on their own, what does halfway between them look like (f(2.5))? My guess is a random smattering of dots that doesn’t look particularly like either, but only one way to know for sure.

To finally conclude this post: One of the coolest things I figured out through this process was that 1 with any number of trailing zeros is the only number that does the same thing in all bases. I count it as trivial math, which means it’s kind of self-evident and not much of a discovery (multiplication by 1 with a number of zeros following it is part of how bases are defined in the first place), similar to x * 0 = 0, but it’s still cool. The friend I was working on this with had a new favorite number after we finished: 10. One-zero, not ten!